But what if we don’t, are we failures, and are we not truly ‘human’ if we are not conventional in all ways? I could talk about the thoughts and questions A Little Life gave me for days and days. She also looks at how society has expectations for us from birth we should all be able to endure anything, we should all want success and riches, we should all have the best relationships possible of all kinds, we should all love sex, we should be grateful to be alive, we should all be survivors. And there is so much Yanagihara looks at pleasure vs. “I’m lonely,” he says aloud, and the silence of the apartment absorbs the words like blood soaking into cotton. Her writing, whilst admittedly (and she has said intentionally) making everything a little extreme, has an honesty about the things we like to talk about and also the things that we don’t which I found impressive and often heartbreaking because we have all felt or thought these things. Yet this is one of the things that Yanagihara seems to want to look at.

He saw Willem looking at his hand and pulled it into his lap. “I’m really sorry, Willem,” he said, so softly that Willem almost couldn’t hear him. He was about to speak when Jude put down the water glass he’d been using as a pastry cutter and looked at him. Here Jude sat after what was, he could now admit, a terrifying night, acting as if nothing had happened, even as his bandage-wrapped hand lay uselessly on the table. Jude shrugged, and Willem felt his annoyance quicken into anger. Yes it makes for disturbing reading, yet I have never understood the psychology behind it before as I have reading this. For example in order to escape the almost constant pain, Jude often (to the horror of those who know about it Willem, Jude’s physician Andy and his mentor Harold) uses the release of self harm. How does someone cope with having been abandoned and then physically and sexually abused? How does someone make a success of their lives after that? How do they survive? These are some of the many questions that Yanagihara asks and some of the answers are not comfortable ones. Without giving too much away, and I think it has been discussed quite a lot all over the shop, we look into his background, the horrendous abuse that he endured and the physical and mental scars it has left and which he is still dealing with now. It is Jude who fairly soon becomes the focus as the novel and it is here that A Little Life starts to take its, now infamous, darker turns. He knew that Jude would be and had been fine without him, but he sometimes saw things in Jude that disturbed him and made him feel both helpless and, paradoxically, more determined to help him (although Jude rarely asked for help of any kind.) They all loved Jude, and admired him, but he often felt that Jude had let him see a little more of him – just a little – than he had shown the others, and he was unsure what he was supposed to do with that knowledge. He loved him – that part was simple – and feared for him, and sometimes felt as much his older brother and protector as his friend. If you are thinking ‘oh right, it is another of those New York novels about successful men’ whilst rolling your eyes, you would be wrong as Yanagihara weaves in various question marks about all of these men and the darker parts of their personalities and pasts, particularly into the unknown and almost mysterious psyche of Jude who never gives anything away, not even snippets, of his youth. Initially the novel traces how the four men meet, how their friendship develops and then how their lives and careers in the big smoke unfold.

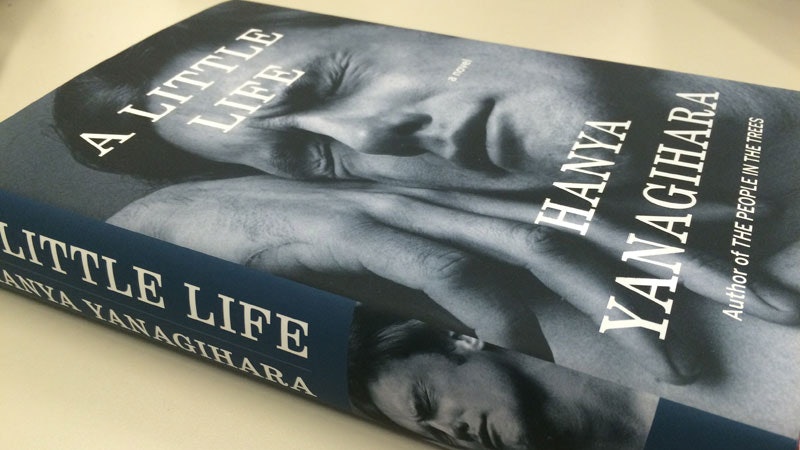

As it opens it seems to be the tale of four men who become friends in college, we watch as they struggle (well three of them do) to make successful lives in New York Willem as an actor, JB as a photographer, Malcolm as an architect and Jude as a lawyer. Picador Books, 2015, hardback, fiction, 736 pages, kindly sent by the publisherĪ Little Life is one of those books that slightly fool you from the start.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)